Project C-43: the lost origins of asymmetric crypto

Alice lives two doors down from Bob.

They speak to each other over a tin-can telephone,

with a taut string running from Alice’s window to Bob’s.

But months later,

Alice discovers a second line tied to it,

running into Eve’s window!

Eve has been listening in!

Appalled, Alice visits Bob with the news.

What can they do to defeat Eve’s wiretap?

Alice suggests that they use a secret code.

But Bob has an entirely different plan!

“Here’s what we’ll do,” Bob says.

“I’ll play loud white noise at my end.

With all that noise on the line,

Eve won’t be able to hear you speak.

But I’ll be able to,

using my new noise-cancelling headphones!”

Arguably,

Bob has just invented asymmetric cryptography!

Bob’s noise source is his private key.

The method is “asymmetric” because

Alice does not need to know Bob’s key;

she just encrypts her message by speaking over the noise.

But couldn’t Eve defeat this with her own noise-cancelling headphones?

No!

Noise-cancelling headphones work

by taking a noise source,

and playing the right anti-noise to cancel it out.

Bob’s headphones can play the right anti-noise,

because they’re next to Bob’s noise source.

But Eve’s noise-cancelling headphones can’t,

because they’re out of range of Bob’s loudspeaker.

This obscure encryption method was described in October 1944 by a Walter Koenig Jr,

who compiled a report on Project C-43,

a secret wartime research project on “speech privacy.”

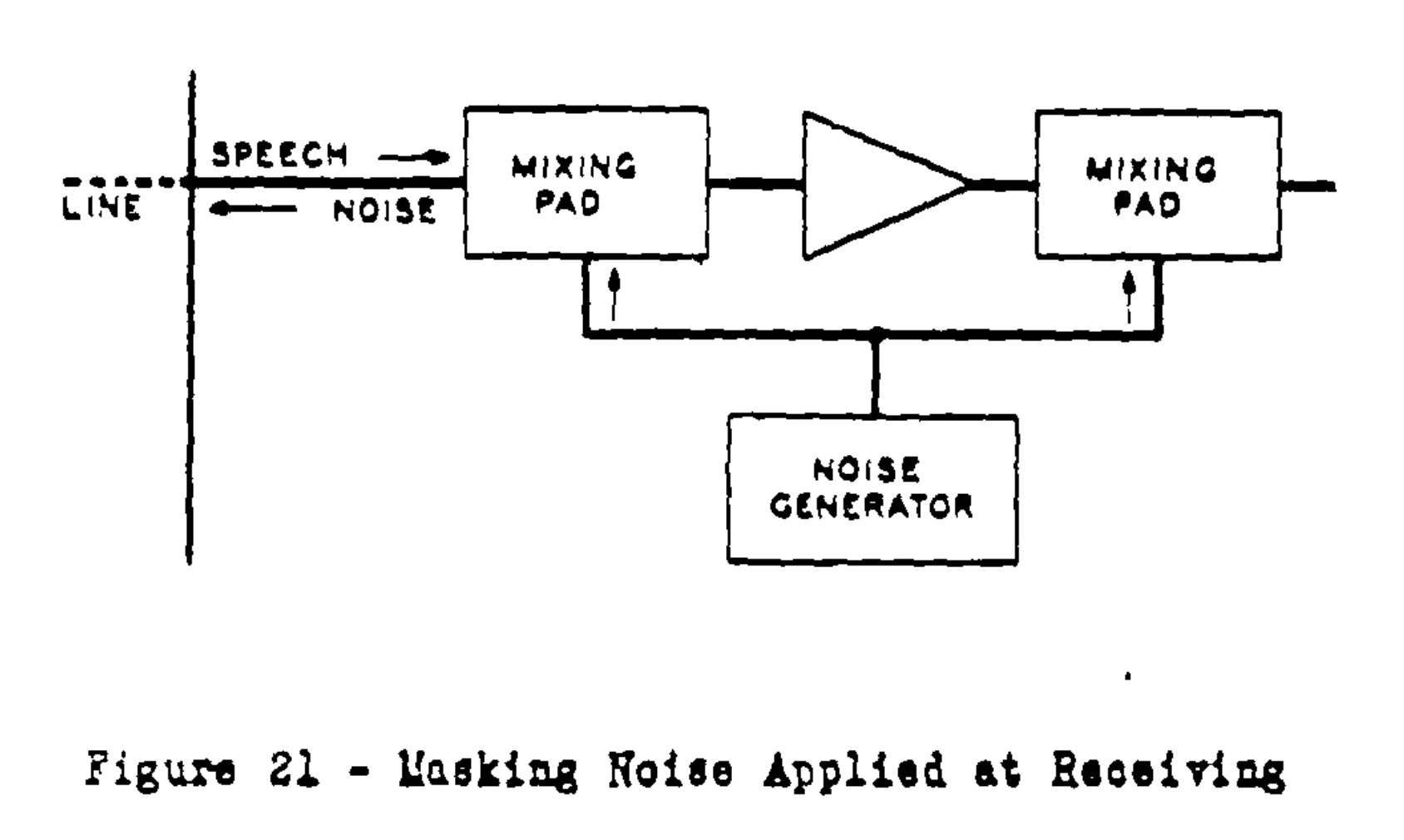

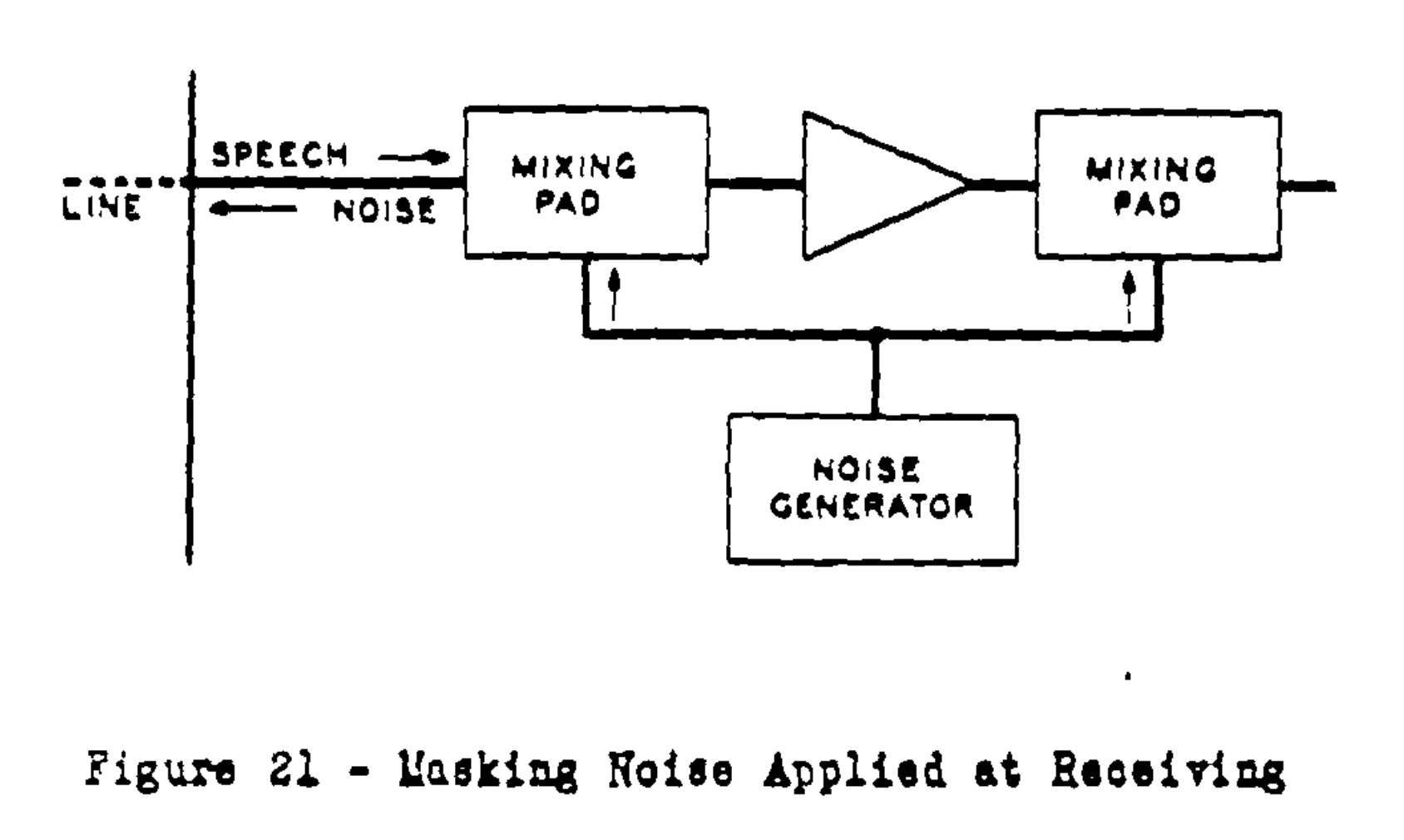

In Section 9, “Masking Systems”,

Koenig writes that

One of the first schemes which is

likely to occur to a person considering how to make speech private

is to add noise or other disturbing signal to the speech

and remove it at the other end,

in other words, to mask the speech.

[... But in another] system,

noise is added to the line at the receiving end

instead of at the sending end.

Again, the noise can be perfectly random.

Since the noise is generated at the receiving end,

the process of cancellation can, theoretically, be made very exact.

From Koenig’s almost-lost observation,

we can trace an unbroken line

through to modern asymmetric encryption algorithms!

The document apparently moldered, unread, for 25 years,

before it was picked up by James Ellis at GCHQ.

Inspired by Koenig’s report,

Ellis wrote in another secret paper,

The possibility of secure non-secret digital encryption,

that

An ingenious scheme

intended for the encipherment of speech over short metallic connections

was proposed by Bell Telephone Laboratories [i.e., Koenig’s paper]

in which the recipient adds noise to the line

over which he receives the signal.

...

The above system is essentially analogue ...

The problem with which we are now concerned is that

of trying to find a digital system which is non-secret ...

We shall now describe a theoretical model

of a system which has these properties.

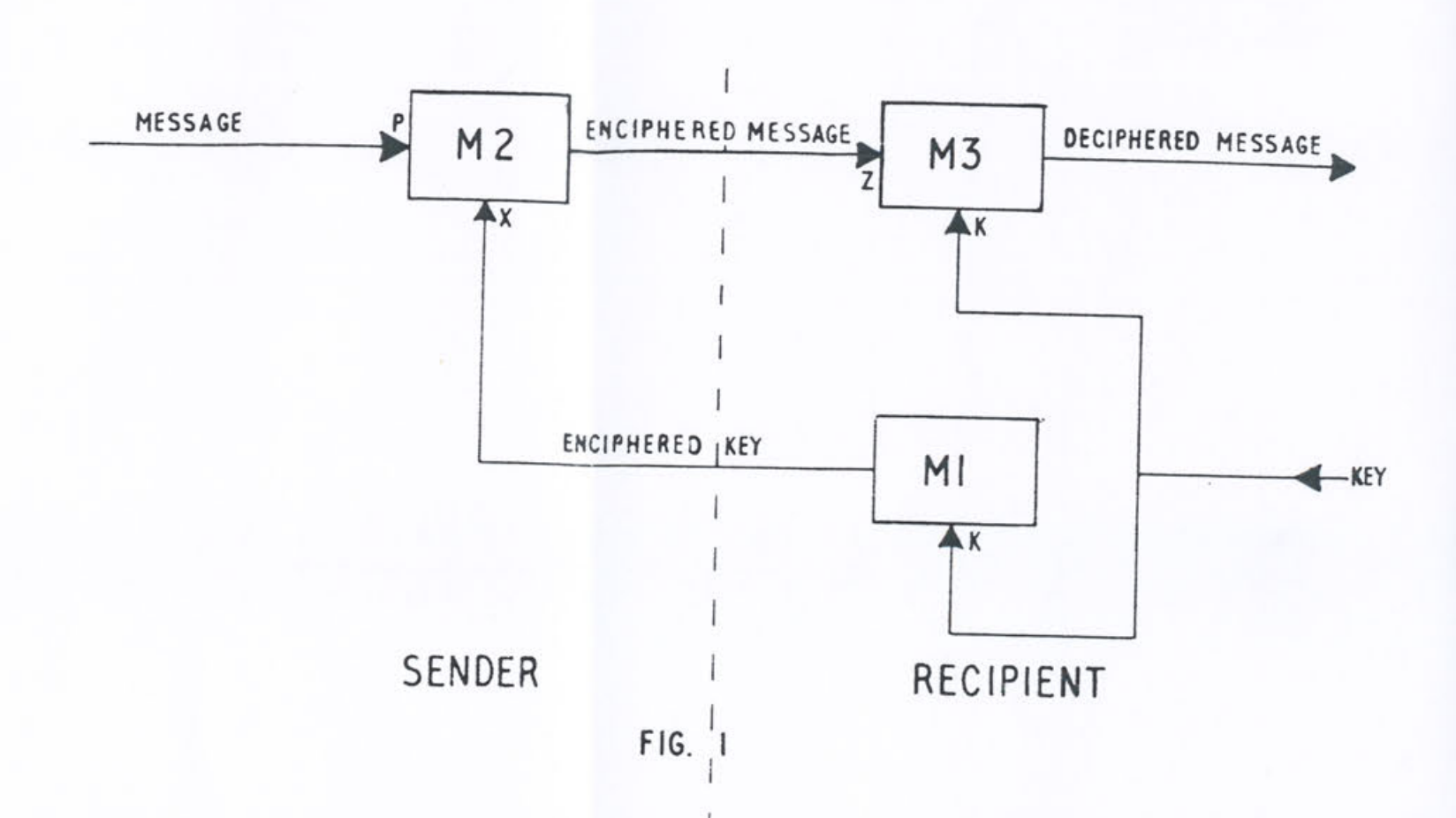

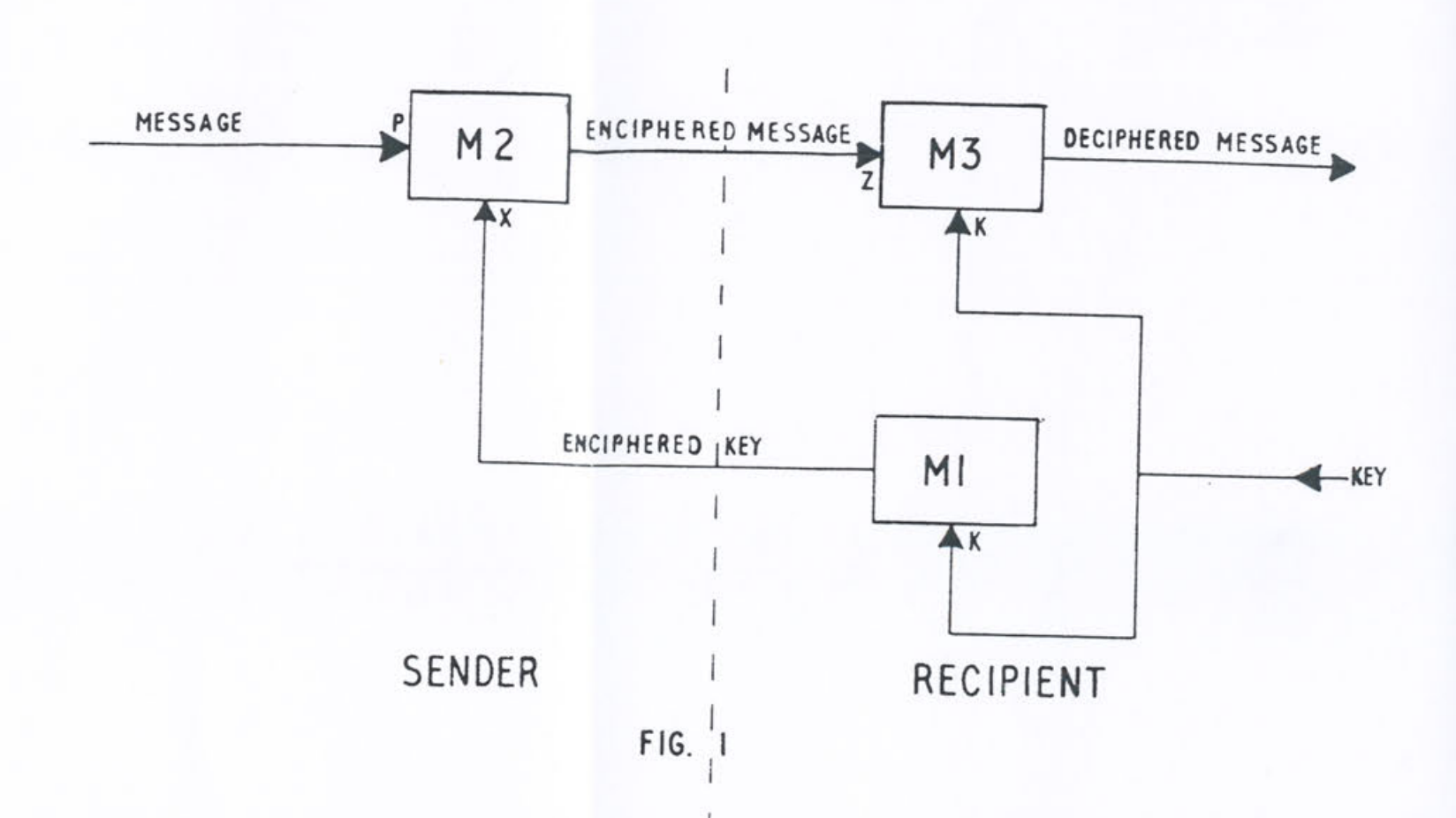

Ellis sketched,

in a diagram resembling Koenig’s,

three machines M1, M2, and M3.

These would derive a public key, encrypt, and decrypt.

He described how to implement these using impossibly large lookup tables,

but was unable to find a practical solution.

Three years passed until

a young Clifford Cocks finished the job

in a sparkling secret one-pager.

Ellis and Cocks’ work was declassified in 1997,

and by now is well-known.

But the legacy of Walter Koenig Jr is almost lost,

the signal drowned by noise generated about an unrelated Star Trek actor.

And, since Koenig’s report was a compilation of many people’s work on Project C-43,

we’ll probably never know

which bright spark had the idea of adding noise

“at the receiving end, instead of at the sending end.”

Similar posts

A history of time in 40,000 pixels

A visualization of how frequently different years are referenced in writing over time, showing patterns in how the past and future are viewed. 2018-12-18

The good old 1955s

2012-04-16

The hacker hype cycle

I got started with simple web development, but because enamored with increasingly esoteric programming concepts, leading to a “trough of hipster technologies” before returning to more productive work. 2019-03-23

How Hacker News stays interesting

Hacker News buried my post on conspiracy theories in my family due to overheated discussion, not censorship. Moderation keeps the site focused on interesting technical content. 2019-01-26

My parents are Flat-Earthers

For decades, my parents have been working up to Flat-Earther beliefs. From Egyptology to Jehovah’s Witnesses to theories that human built the Moon billions of years in the future. Surprisingly, it doesn’t affect their successful lives very much. For me, it’s a fun family pastime. 2019-01-20

I hate telephones

I hate telephones. Some rational reasons: lack of authentication, no spam filtering, forced synchronous communication. But also just a visceral fear. 2017-11-08

More by Jim

What does the dot do in JavaScript?

foo.bar, foo.bar(), or foo.bar = baz - what do they mean? A deep dive into prototypical inheritance and getters/setters. 2020-11-01

Smear phishing: a new Android vulnerability

Trick Android to display an SMS as coming from any contact. Convincing phishing vuln, but still unpatched. 2020-08-06

A probabilistic pub quiz for nerds

A “true or false” quiz where you respond with your confidence level, and the optimal strategy is to report your true belief. 2020-04-26

Time is running out to catch COVID-19

Simulation shows it’s rational to deliberately infect yourself with COVID-19 early on to get treatment, but after healthcare capacity is exceeded, it’s better to avoid infection. Includes interactive parameters and visualizations. 2020-03-14

The inception bar: a new phishing method

A new phishing technique that displays a fake URL bar in Chrome for mobile. A key innovation is the “scroll jail” that traps the user in a fake browser. 2019-04-27

The hacker hype cycle

I got started with simple web development, but because enamored with increasingly esoteric programming concepts, leading to a “trough of hipster technologies” before returning to more productive work. 2019-03-23

Project C-43: the lost origins of asymmetric crypto

Bob invents asymmetric cryptography by playing loud white noise to obscure Alice’s message, which he can cancel out but an eavesdropper cannot. This idea, published in 1944 by Walter Koenig Jr., is the forgotten origin of asymmetric crypto. 2019-02-16

How Hacker News stays interesting

Hacker News buried my post on conspiracy theories in my family due to overheated discussion, not censorship. Moderation keeps the site focused on interesting technical content. 2019-01-26

My parents are Flat-Earthers

For decades, my parents have been working up to Flat-Earther beliefs. From Egyptology to Jehovah’s Witnesses to theories that human built the Moon billions of years in the future. Surprisingly, it doesn’t affect their successful lives very much. For me, it’s a fun family pastime. 2019-01-20

The dots do matter: how to scam a Gmail user

Gmail’s “dots don’t matter” feature lets scammers create an account on, say, Netflix, with your email address but different dots. Results in convincing phishing emails. 2018-04-07

The sorry state of OpenSSL usability

OpenSSL’s inadequate documentation, confusing key formats, and deprecated interfaces make it difficult to use, despite its importance. 2017-12-02

I hate telephones

I hate telephones. Some rational reasons: lack of authentication, no spam filtering, forced synchronous communication. But also just a visceral fear. 2017-11-08

The Three Ts of Time, Thought and Typing: measuring cost on the web

Businesses often tout “free” services, but the real costs come in terms of time, thought, and typing required from users. Reducing these “Three Ts” is key to improving sign-up flows and increasing conversions. 2017-10-26

Granddad died today

Granddad died. The unspoken practice of death-by-dehydration in the NHS. The Liverpool Care Pathway. Assisted dying in the UK. The importance of planning in end-of-life care. 2017-05-19

How do I call a program in C, setting up standard pipes?

A C function to create a new process, set up its standard input/output/error pipes, and return a struct containing the process ID and pipe file descriptors. 2017-02-17

Your syntax highlighter is wrong

Syntax highlighters make value judgments about code. Most highlighters judge that comments are cruft, and try to hide them. Most diff viewers judge that code deletions are bad. 2014-05-11

Want to build a fantastic product using LLMs? I work at

Granola where we're building the future IDE for knowledge work. Come and work with us!

Read more or

get in touch! This page copyright James Fisher 2019. Content is not associated with my employer. Found an error? Edit this page.

Granola

Granola